“Faire une architecture, c’est faire une créature”, wrote Le Corbusier in 1955 in his Lithography Portfolio “Le poème de l’angle droit” – to build meant to create a living being, to lend physicality to a structure and in this way to rise above the purely functional. With this stance, LC aimed for “the highest value in life: the poetic.” In doing so, the architect Le Corbusier depended upon the artist Le Corbusier: the latter’s persistent practice of art for its own sake, the daily struggle at the studio to find form, proportion, and harmony help the architect in his search for aesthetic expression.

Already at the very beginning of his career, at the start of the 1920s, it was impossible for Le Corbusier to separate architecture and painting. For him, they were the two means of expression based upon the division of space. The basic question of how to divide space – that of a house just as much as that of a city – was now what concerned him, at the brink of Modernism. He was aware of the new technical developments and economic conditions that would emerge out of the era of the machine and mass production, as well as the needs of the individual and the new possibilities in construction that would arise therefrom.

The conclusions which Le Corbusier came to in his awareness of these dramatic changes placed architecture on a new foundation: discarding the past, he replaced it with answers to questions that had never once been asked in such radical coherence. “A house is a machine in which to live,” he wrote in 1921 – and meant no less than that a house had to be strictly planned according to a scale of human needs, clearly partitioned, functional, offering refuge to the individual.

But by the end of the 1920s, his purism and striving for the optimum use of all possible resources no longer satisfied him. In opposition to the zeitgeist, he began to accentuate the tension between structures instead of highlighting their formal harmony, giving them a marked sculptural form rather than standardizing them. From now on, organic forms were an integral part of his work, he composed and modulated, and as the poetic quality gained importance, he breathed life into Modernism.

So the legacy of the architect Le Corbusier lies first of all in his coherence, which made him into the propagandist for modern architecture par excellence. Almost more central today, however, are both his particular way of thinking a project and his social concerns, in respect to which he had a pioneering role in their formulation and implementation. His objective was not simply “architecture” or “art” – his objective was life itself. And for this reason, Le Corbusier is, and will continue to be, thoroughly relevant.

T. Rabara

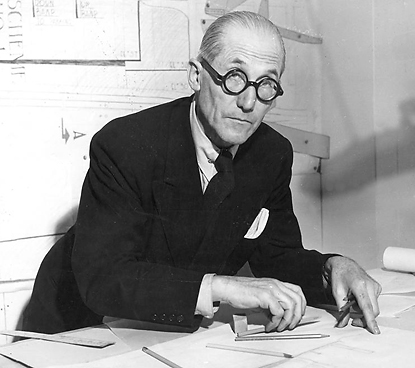

Le Corbusier in 1947 working on

the draft of the UN headquarters.

© United Nations Permanent

Headquarters; FLC / 2019, ProLitteris, Zurich